Born in the shadow of Normandy’s rolling hills and the great Norman court, Matilda arrived on 7 February 1102 as the firstborn daughter of King Henry I of England and his queen, Matilda of Scotland. From her cradle, her destiny was entwined with the fate of two kingdoms. Her parents, keen to secure their line after the conquest of 1066, have left us the promise of Henry’s hopes for a fifth Plantagenet king. Yet when Matilda was just eighteen years old, that promise shattered on 25 November 1120, in the icy waters off Barfleur, where the White Ship went down. On board was young William Adelin, Matilda’s only legitimate brother and the golden hope of England’s future. His death, alongside two hundred and fifty others, tore an endless chasm into Henry’s plans: suddenly, Matilda stood alone as his sole legitimate heir, a woman in a realm that had never known a ruling queen.

Henry, determined that his daughter succeed him, made his barons swear oaths of fidelity to her, but the Norman lords murmured behind their hands. A woman on the throne would be—so they thought—an affront to precedent and God’s order. Yet, for the next fifteen years, Matilda grew in both mind and stature. Though she carried the title “Empress” by her earlier marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, her greatest trials lay ahead on the windswept moors of England, not the marble palaces of Rome. When Henry I breathed his last on 1 December 1135, the barons seized the moment’s frailty: her cousin, Stephen of Blois, slipped into Winchester Cathedral and took the crown, drawing down the golden circlet that rightfully belonged to Matilda’s brow.

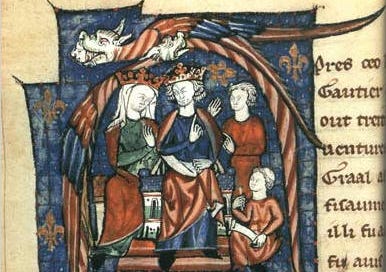

Hearing the news from Normandy, Matilda’s heart hardened like the iron gates that protected her father’s castles. In 1139, she resolved at last to claim her inheritance. Across the Channel, she landed with a small force, her banner bearing a golden lion on red, and marched southward. At her side rode two loyal champions: her half-brother Robert, Earl of Gloucester, whose arm was as strong as his loyalty, and her uncle, King David I of Scotland, whose Highland warriors bore tartans of blue and white. Together, they laid siege to key fortresses, hoping to starve out Stephen’s supporters and rally the nobles who still remembered Henry’s oath.

It was early in 1141 that fate’s wheel turned most sharply. On a bleak February morning near Lincoln, Matilda’s forces shattered Stephen’s army, and the king found himself imprisoned in the cold stone of Lincoln Castle. The streets of London hummed with expectation: women murmured of crowning Matilda at Westminster Abbey, and young knights sharpened their swords in anticipation. Yet when she appeared at the gates of London, a roar of disapproval greeted her—a queen too haughty, they said, a woman unfit to wear a crown. And so the capital’s gates stayed closed to her, and her coronation collapsed beneath the weight of baronial scorn.

Though letters from her court proclaimed her “Lady of the English,” her hold on power proved as impermanent as spring’s first thaw. Her half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, led her armies from battle to siege, but in September 1141, fate again intervened at Winchester. As Matilda’s army encircled the city, Queen Matilda of Boulogne—Stephen’s fierce wife—rallied a relief force. Trapped, Robert’s men clashed with the queen’s vanguard, and amid the shouts and clang of steel, Robert himself was cut off and captured. With her chief marshal in chains, Matilda faced a grim bargain: free Robert or hold Stephen. To the dismay of her supporters, she chose family over crown, and Stephen rode free once more, returning to reclaim the throne.

From that moment, the war’s tide ebbed and flowed with neither side able to deliver a final blow. Fortresses changed hands like tokens in a child’s game; river crossings and ravines became graveyards of men. In 1147, Robert of Gloucester succumbed to illness and died in Bristol, leaving Matilda with only her resolute spirit and a son, Henry, born years before at Le Mans. Bereft of her greatest ally, she withdrew to Normandy, where her husband, Geoffrey of Anjou, fortified their hold on the duchy. There, among the grey ramparts of Rouen, she watched as Henry, now fourteen, learned the art of kingship in his father’s court.

By the summer of 1153, England lay weary and broken beneath fifteen years of skirmish and starvation. In the fields around Wallingford, Stephen’s forces and Henry’s Angevins paused before a pitched fight that both knew would only bring more ruin. Mediated by bishops and barons longing for peace, a truce took shape in Winchester Cathedral that November. Stephen, binding his last hope, recognised Henry Plantagenet as his adopted son and heir; in return, Henry swore homage to Stephen and pledged to maintain the realm’s peace. Though Stephen would wear the crown until his death in October 1154, it was young Henry who rode at his funeral in London, a sword at his hip and the promise of a new era in his eyes.

Empress Matilda never again set foot in her father’s kingdom of England. She died in Rouen on 10 September 1167, her grey eyes witnessing the dawn of her son’s reign as Henry II. Though she never wore a crown of England, her unbending will and the oaths sworn in her name laid the foundation for the Plantagenet dynasty that would last more than three centuries. In the rolling fields of Normandy and the echoing halls of Westminster, the memory of “Maud, Lady of the English” endures—a testament to a woman who dared, in a man’s world, to challenge the sky.

#EmpressMatilda, #TheAnarchy, #MedievalHistory, #EnglishMonarchy, #PlantagenetDynasty, #WomenInHistory, #CivilWar

Share this post